The Philadelphia Story: Sleepless in Starkville

by Kathryn M. Barber

I can’t sleep anymore. Two months into the pandemic, I lost the ability to turn my mind off at night. I sit up awake in my living room, watching reruns of shows I’ve already seen a hundred times over, hoping the lack of suspense and drama will lull me to sleep. It doesn’t. I take melatonin. I make tea. I buy a supplement from a friend who harvested her own passionflower and chamomile oils. I listen to sleep sounds, rains on canvases. I pretend I’m in a tent back home in the Smoky Mountains. I pretend 45 isn’t president, that we live in a society and a world that doesn’t need protests. That we love people for who they are, where they are. That there isn’t another black man murdered in another city every couple of weeks, another protest for basic rights that shouldn’t need protesting in the first place. That we don’t care who someone’s lover is, what color their skin is, what country they came from, whether or not they want to be a mother or a wife. I pretend our laws reflect all of this love. I pretend Michelle Obama’s words that night a few weeks ago penetrated every heart in the country, changed them, like the blackest of coal turned into princess-cut diamonds; that everyone wept as I did. I pretend Ruth Bader Ginsberg makes it long enough to see Joe Biden elected, that we mourn her from the other side of November.

With every rubber bullet, every blast of tear gas, with every reported remark from Mitch McConnell, the more I wake up at night, the longer I lay there begging sleep to come back to me. I know the privileges I have in this country. I understand the structures that put them into place and gave them to me. I feel trapped in my home, a home I’m grateful to have. 2020 has felt like watching a show or a film. We’re bystanders, watching the climaxes unfold again and again, screaming at the players to do something different this time. But they don’t.

The last time I slept hard, good, woke up rested, was at a friend’s house in Wilmington, North Carolina, back in March, just before schools scrambled to transition to online instruction, masks became mandatory fashion staples, and I still loved meandering aimlessly the endless aisles of Kroger.

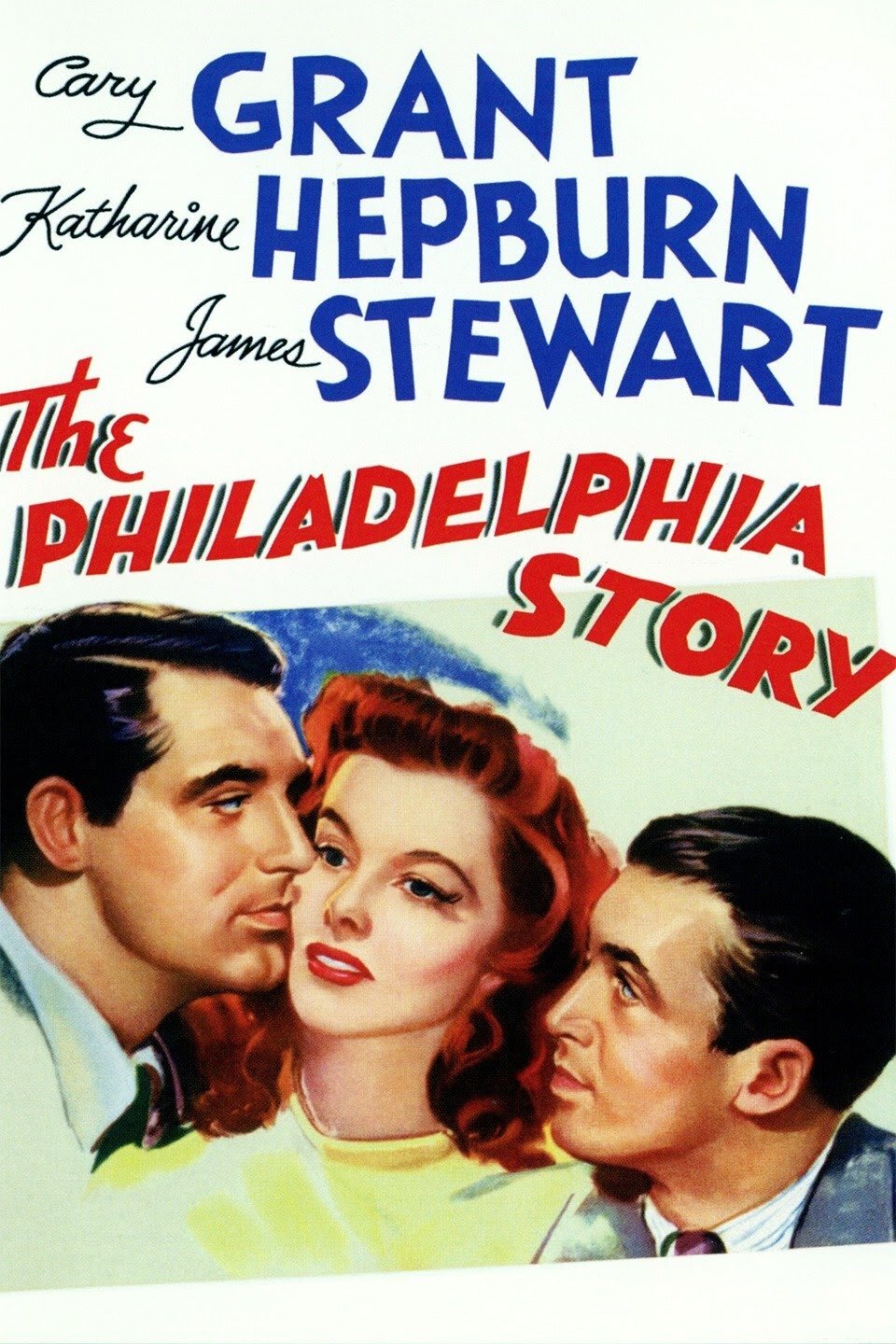

In absolute surrender, I rewind The Philadelphia Story, hit play on my VCR. I listen as the tape winds and winds and winds. It stops, clicks forward, and the sound of MGM music sinks into the darkness of my bedroom. When I first began developing an interest in old movies, back in high school when we watched Casablanca as part of our World War II education in junior history, my favorite uncle gifted me his entire collection of Cary Grant films on VHS. Since then, something about the sound of Cary Grant’s even tone, his voice, his presence—though half his character roles are misogynists—could persuade my mind to stop, switch off, go black. It entrances me.

I’m out before Tracey Lord’s father even shows up uninvited to the wedding.

And I ask myself: what about this film puts me to sleep? I’m still waking up four, five, six times a night, but I’ve given up on my sound machine, on the hum of frogs outside my bedroom window. The only thing that puts me to sleep now is the sound of Cary Grant arguing with Katherine Hepburn, interrupted by the ramblings of Jimmy Stewart. In many ways, it’s both a feminist and anti-feminist film. At the start, we see Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant in a great fight. She throws his golf clubs out the door. Her sister asks her mother in the first few minutes of the film “Did he really sock her, Mother?”

“Don’t say sock, dear,” Mrs. Lord replies. “Strike is quite an ugly enough word.”

And by the end, Katherine Hepburn realizes her one true love is, in fact, not her intended husband, around whose wedding the film is set, and it isn’t newcomer Jimmy Stewart, who plays writer Macaulay (Mike) Connor. It’s her first husband, C. K. Dexter Haven, played by Cary Grant. Of course, we’re meant to view their love as true love, the kind you leave behind when you’re a child, and then you grow up and remember, oh hey, they weren’t so bad. I guess he is the one for me.

At the same time, many of Katherine Hepburn’s lines feel out of place and ahead of their time for a film made in 1940. At the film’s beginning, Tracey and her mother are discussing their failed marriages. While Tracey’s mother sounds regretful, Tracey is unapologetic and firm in her divorce:

Mrs. Lord: “Neither of us has proved to be a very great success as a wife.”

Tracey: “We just picked the wrong first husbands.”

Mrs. Lord: “Don’t let’s argue about it. You wanted me to take stand, so I did.”

Tracey: “It’s the only thing a woman could do and keep her self-respect.”

Mrs. Lord: “Yes, dear, I know. Now I have my self-respect and no husband.”

Tracey: “You almost talk as if you wanted him back.”

Mrs. Lord: “He wouldn’t come back probably.”

The idea of a woman privileging her self-respect over a husband is certainly not the prevailing idea in most forties films. I read a review once that said Katherine Hepburn “sizzled off the screen,” and she does. Something about her strength, eighty years ago, insisting that self-respect is more important than a husband, makes me feel more comfortable about the empty space in my own bed.

But why this film? Why this forties romantic comedy where the woman, in the end, ends up right where she started? With all the trauma in my head everyone keeps saying we aren’t processing in the year of COVID—why is this the film that seems to quiet those waves, drown out all the headlines I spend hours scrolling through, all the biased articles I try to piece together to sort out the true stories? I think every day about the history books my nieces and nephews will use in fifth-grade social studies one day. What will they say? What will they leave out? Will they interview me, asking me what it was really like back then? And what will I say? It doesn’t feel like “trauma” right now; it feels like unrest. Like sadness. It’s heavy and sticky and I can feel the weight of it, but I keep hearing we won’t all process this for a long while yet. So what about Tracey Lord and C. K. Dexter Haven lulls me backward, tips me out and empties my head of worry and racing thoughts, if only to sleep for three hours straight?

When I first saw this film, I had just lost my home in Hurricane Florence. For nearly a month, S. E. Harsha and I sat huddled on my mother’s living room couch in Tennessee, watching the news, screaming tearfully at friends back in Wilmington on the phone who refused to leave. We cried on the back porch, wondering what kind of home we would return to. We got texts from friends who tried to make it home, but found parts of 40 and 95 washed away. We saw photographs of roads broken and open, ready to swallow cars whole. I had five days to gather what hadn’t been damaged in my apartment and move. The ceiling above mine had already fallen in. They said mine was next.

I’d lived in this apartment for six weeks, had just finished unpacking. I packed it all back up, and friends helped me empty its contents into a storage unit on Carolina Beach. I spread myself across three living spaces: my bed and a heap of boxes I moved into a kind friend’s spare bedroom across the hall from his roommate, whom I’d never met; for nights alone, a regular at the restaurant where I waited tables gave me the key to her second home. Two friends from undergrad had ended up in Wilmington, too, and they offered their spare bedroom in exchange for my dog-sitting while they were on a mission trip in Guatemala.

It was in this last home I remained for the majority of the next six weeks. I was used to sleeping with the television on, a habit I’ve tried for years to break. There was no television in their spare room, so I pulled up an app on my phone—it was this sort of Netflix for old movies that was shut down just a few weeks later. I longed for the voice of Cary Grant to sing me to sleep.

I picked The Philadelphia Story because of the cast. I had it on VHS, though I’d never watched this one. I could quote back to you the first twenty minutes before I ever saw the end. For weeks, I never made it to the end of the film. Tracey, her sister, and her mother would banter about ex-husbands and Tracey’s upcoming wedding. Macauley Connor would be assigned a story for Spy magazine to cover the no-press-allowed wedding of socialite Tracey Lord. “I’m gonna tell Sidney Kidd very plainly I’m a writer, not a society snoop!” Connor raves. “Let Kidd fire me! I’ll start writing short stories again; it’s what I should be doing anyway.” And I’d think to myself as I began to drift off in that sweet house that rested in my favorite corner of Wilmington: I should be writing short stories, too. But I couldn’t have written a lick of anything then, not even if I’d wanted to. It’s how I feel now, in the middle of this ongoing, everlasting pandemic: I should be writing short stories, but I can’t. I can’t write anything.

I admired almost everything about this film: the banter, the wit, the punchy dialogue. I couldn’t choose ten favorite quotes if I tried. Excepting the painfully predictable and cringy ending of a woman returning to a first husband who, by her own mother’s declaration, “was very mean to her, my dear,” it’s the sort of thing I wish I could write. Tracey Lord, once married to C. K. Dexter Haven, now engaged to George Kitteridge, who almost for a second might fall in love with Mike Connor, who is loved dearly by Elizabeth Imbrie—forget love triangles, it’s a love pentagon.

When I think about Hurricane Florence, I remember moving in slow motion. I never stopped. I didn’t just teach my classes that semester; I took on the class of a colleague who couldn’t finish out the remainder of their semester. I didn’t just teach those classes; I waited tables on weekends and went home to grade papers after. I kept moving because standing still was not an option. Not surviving Florence was not an option. It felt like shit. I cried a lot. I fought with family members who didn’t understand how I felt, who insisted I had a place to live and I could ask for nothing more. It didn’t feel like trauma when I was told I had to move. It didn’t feel like trauma watching those waves pour down on the shores of Wrightsville Beach or when the Cape Fear River swelled high enough to hide away Water Street entirely. It didn’t feel like trauma until much later, when I finally found a sweet orange house downtown and sat still a while.

I moved my things into a storage unit and scattered myself across the homes of three friends, staying wherever felt the most stable for my mind that night. But it didn’t feel like that—it didn’t feel like asking myself, where will you feel best tonight? I just went. Sometimes, it was the apartment of that sweet regular customer from the café, whom I loved like an aunt. Sometimes, it was an acquaintance’s spare room and my own bed. Most nights, it was the love inside a house owned by the guy who sat in front of me in German 2 in undergrad, all the way back in East Tennessee, and his wife, who became one of the dearest friends I’ve ever known. But no matter where I laid my head, Tracey Lord came with me.

Some nights, I get as far as the scene where Tracey’s father shows up. He hasn’t been invited to the wedding, something Tracey’s mother calls “good and stinky.” Tracey’s rather sore at him, as he’s been taking up with a dancer up north—the root of the blackmail plot from Spy magazine: if Tracey doesn’t allow Mike to write about her wedding and Elizabeth Imbrie to photograph it, Sidney Kidd will run a story about Tracey’s father. Seth Lord begins to explain to both Tracey that the right kind of daughter is “full of warmth for him, full of foolish, unquestioning, uncritical affection.” He tells his daughter that while she has a good mind, a pretty face, and a disciplined body—everything it takes to make a lovely woman—she’s missing the one essential thing: an understanding heart. “And without that,” he tells her, “you might as well be made of bronze.”

“That’s an awful thing to say,” she tells her father. She asks him if he’s suggesting his affair is her fault, then, if he means to say her performance as a daughter is to blame for Tina Mara, the dancer up north.

“To a certain extent, I expect you are,” he says. “But better a prig or a perennial spinster… however many marriages,” he tells his daughter. It doesn’t matter who comes for her: her father, her mother, Spy magazine. Tracey Lord is unapologetically Tracey Lord. And in a way, it’s like she is made of bronze—but I think of this in a much different way than her father does. To him, women must be check marks in boxes. They’re a laundry list of characteristics and traits. If you are not this, then you are not woman. If you do not behave, then you are not woman. I think Tracey Lord is made of bronze. You can build cities out of bronze. Wood burns and breaks, turns to ash. Stone can crumble. Bronze may melt, but it doesn’t turn to ash or pebbles. It remains bronze.

Later in the film, Mike Connor tells C. K. Dexter Haven that a man “does expect his wife to behave, naturally.” C. K. Dexter Haven responds with, “Yes, a man does expect his wife to behave naturally.” There’s so much loaded into that one comma: “behave, naturally” versus “behave naturally.” Tracey Lord behaves naturally, even if that doesn’t always mean “behaving.”

Rain and hurricanes do not destroy bronze. Neither do pandemics or viruses. Tracey Lord is wonderfully made of bronze, and she won’t be made of anything else because she’s told to be. This idea of a headstrong woman isn’t new, of course, now—but for a 1940 film, depicting the heroine in this way wasn’t common. Not only is Tracey a divorcee, but so is Elizabeth Imbrie, the photographer, we find out. As Tracey questions Elizabeth and Mike about whether or not they’re involved, it comes to light that Liz has been married before, and Mike was unaware of it. “You’re the darndest girl, Liz,” he says. But Liz, like Tracey, is unfazed by this comment meant to be insulting. “You never asked,” she says simply.

Both Tracey and Liz take control of the men in their lives without apologies or pleasantries. They survive. They carry on. They drink and they’re accused of scandal, and they shrug it off. Then they drink more champagne.

And so I still can’t say quite why this film relates to the trauma of COVID-19 or the racial unrest at play in 2020. I can’t say why this is the film that calmed me for so long after a hurricane took my home. I still don’t know why for the six weeks I lived with friends, desperately searching for a home in the middle of a housing crisis, eventually taking a home far more expensive than my adjunct and waitress pay could afford—this is the only film that could rock me to sleep. I think about my relationships to my life and the films or shows I’m watching often, and they usually make more sense: why when I was torn between a new life and the boy back home, I chose the boy back home after watching Sweet Home Alabama once a week while living in London. All the reasons Casablanca is my favorite film. Why it’s still hard for me to watch Beauty and the Beast because it reminds me too much of a little girl I loved desperately, of whom I had to let go. I slip inside television screens when the world is too much for me, but often, there’s a correlation between what’s happening in my/the world and what digital escape I choose. Sometimes it’s a sense of place: I watch Dawson’s Creek when I miss Wilmington, Smallville because it recalls high school memories, the first three seasons of Grey’s Anatomy when nostalgia turns into sadness. And I can explain each one of these choices, the correlations between my life and the kinds of comfort these stories and characters bring.

At the beginning of the film, Dinah Lord, Tracey’s much younger sister, exclaims dramatically: “Oh, I wish something would happen. Nothing ever possibly in the least ever happens here.” She follows her lament with the question, “Mother, how do you get smallpox?” As I try to sleep each night, I always smile here at Dinah, and I blame her question for everything that’s happened in 2020. In January of 2020, I moved from Wilmington, North Carolina to Starkville, Mississippi for a teaching job. I still marvel at how the year started with me easing into new classes, returning to former colleagues, starting over in a place I once lived years ago. How I would walk from my office to the Writing Center for my tutoring hours thinking about how calm everything was. Being grateful for it. While I missed the beaches of North Carolina terribly, I appreciated the comfort of knowing I’d never again have to pile my books and movies into closets in hopes they wouldn’t be ruined by hurricane rains, that I’d never again have to assess what to leave and possibly sacrifice and what to fill my car with. Sometimes, this was enough to outweigh not feeling the sand between my toes every weekend. It’s quiet here in Mississippi, I remember thinking: Nothing ever possibly in the least ever happens here.

I don’t know what I’ll say about 2020 when it’s over. Maybe I’ll remember watching nothing but Ava DuVernay films for a week. Maybe I’ll remember trying to focus on my summer work while I track every Black Lives Matter protest reported on the news. Maybe I’ll remember trying to absorb everything Ibram X. Kendi said. Maybe I’ll remember realizing the full extent of what it means to be privileged, that my sleep had never been steadily interrupted. Maybe I’ll remember all the fights people had over wearing masks, or the student who told me she missed an assignment because she fainted twice that day due to her positive diagnosis. Maybe I’ll remember most the isolation. Maybe I’ll remember scrambling to redo my classes, to move them online. And maybe I’ll remember how much, for me, the racial history of America overshadowed COVID in many ways as I’ve struggled to have hard conversations with family, with friends, with myself. That I thought often of how easy, despite what’s going on in the world constantly, I’d been able to sleep up until now. I don’t know. What I do know is that for me, for whatever reason I can’t explain or connect, whatever trauma this is, however it’ll feel when and if it’s all over—when I need to press pause, when I can’t bear to read another news article or explain to another friend why I don’t use Facebook anymore, I rewind that tape over and over and over again.

When I need to press pause, I press play.

TOP TEN QUOTES FROM THE PHILADELPHIA STORY:

“You’ll never be a first-class human being or a first-class woman until you’ve learned to have some regard for human frailty.”

—Cary Grant as C. K. Dexter Haven

“This is one of those days that the pages of history teach us are best spent lying in bed.”

—Roland Young as Uncle Willie

“I thought all writers drank to excess and beat their wives.”

—Cary Grant as C. K. Dexter Haven

“Holy mackerel, what goes on here?”

—James Stewart as Macauley “Mike” Connor

“You haven’t switched from liquor to dope by any chance, have you Dexter?”

—Katherine Hepburn as Tracey Lord

“I can’t afford to hate anybody. I’m only a photographer.”

—Ruth Hussey as Elizabeth Imbrie

“Don’t say stinks, darling, say smells if absolutely necessary. But only if absolutely necessary.”

—Mary Nash as Margaret Lord

Dinah Lord: “[Tracey’s] sort of… hard, isn’t she?”

Margaret Lord: “Certainly not. She just has exceptionally high standards for herself.”

“I’m the perfect gentleman. Except on occasion.”

—Cary Grant as C. K. Dexter Haven

Dinah Lord: “Well, if you’re asking me—”

Tracey Lord: “I’m not.”

Kathryn M. barber

Kathryn M. Barber teaches creative writing and literature at Mississippi State University. Her favorite pastimes are riding her horse and tormenting the farm boy who works there (she also loves quoting movies out of context, like this). She adores black and white and Ingrid Bergman. You can find more of her work in The Masters Review, The Pinch, Moon City Review, Volume 1 of Press Pause, and elsewhere.